How the future almost was…

Gather round, kids, and we’ll tell you about the Golden Age of web design. CSS – Cascading Style Sheets – was a web specification released into the wild just before the turn of the century in 1996.

By 1998, it had matured into CSS2 – at a time when home Internet use was just pulling into the mainstream and a home computer went from a toy for geeks to a necessary utility.

But the web had seen nothing yet. CSS3 hit the shelves in 1999, just in time for the 21st century to take off.

Google was in its infancy, and a couple of years later, blogs – the great common denominator of web participation – became a thing. Suddenly, businesses of every kind were separated into two groups: Those with an online presence, and those who were left out. You did not want to be left out.

The web’s economic boom gave birth to a new job title: “web designer,” and a new moniker: “Web 2.0,” to signify that we could break free of the old naked-HTML standard of jarring color choices and ugly GIFs that dominated the early web from GeoCities to AOL.

But behind this economic boom, while the rest of the world was all too pleased with itself for nurturing a BlogSpot.com account into a book deal based on a recipe diary, web designers were staying abreast of previews in CSS design just around the corner. And they were in awe. It was like beholding the face of God himself.

CSS Zen Garden

In 2003, a little site launched called CSS Zen Garden. It was a unique concept: The site hosted a simple content template, and then users could dump that content into their own custom CSS styled pages and upload them for the showcase. The gallery of top designs, even today, is a jaw-dropping showcase of unimaginable beauty.

There’s a whimsical robot bounding up to greet you before a spinning starburst background. Here’s a 1950s movie theater where the content scrolls up the movie screen. There’s a sports-themed design with a basketball court motif. Here’s a sophisticated art gallery to remind us that, yes, this was the birth of a brand new art form.

It was as if Willy Wonka and his team of Oompa-Loompas had turned to making web pages instead of chocolate bars. Verily, web developers gasped as they oohed and awed at these pretty layouts and clever tricks, this was “the road to enlightenment” to quote the template.

And every design loaded fast and displayed flawlessly… as long as your web browser was named “Mozilla,” “Opera,” or “Safari.” But surely the Internet Renaissance was right around the corner as soon as all of the web browsers united in supporting the full feature set of CSS3. It had to be any day now…

Narrator: It would NOT be any day now!

As web design became a more exciting topic by the hour, designers hopped from forum to forum, sharing links to design inspiration websites and blogs. It was so exciting to think how the web would look when it all came together.

But as the years dragged by with no progress on the web at large, it became clear that we were all being held back by one dominant web browser dragging its feet. The protests against this browser grew louder by the day.

Why we can’t have nice things:

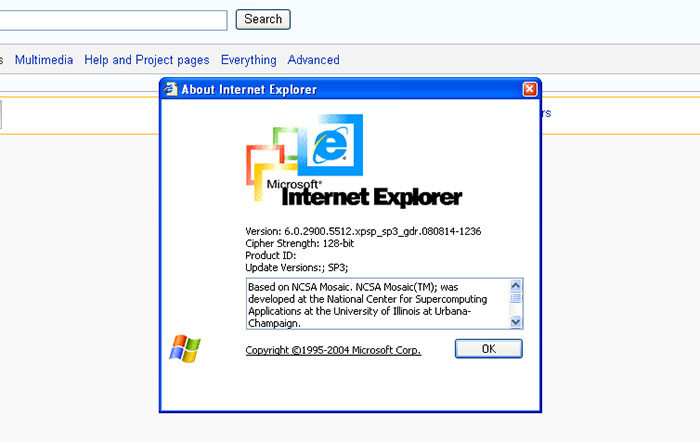

We’re talking, of course, about Internet Explorer. Version 6 came along just in time to ruin the CSS party. Not only did Microsoft not fix any of the issues from IE versions 1-5, but 6 became the world’s standard throughout the 2000s, thanks to shipping by default with Windows XP.

And designers discovered, to their shock and horror, that most consumers do not care about keeping their software updated and patched. To the average Joe User, a computer was something you brought home, plugged in, and did nothing to upgrade or fix until it wheezed its last spin of the CPU fan and died. Then you bought a new computer.

Internet Explorer 6 became the scourge of the web design world. The fact that it rendered CSS designs as if they’d been run through a garbage disposal was just the beginning; it also had gaping security holes that never got patched, allowing disastrous viruses and malware to run rampant on the web. The litany of criticisms against Microsoft’s web browser became a minor civil war during the 2000s. PC Magazine called it “the Great Microsoft Blunder.”

At the peak of the civil war, the Web Standards Project was an effort to wake up Windows users. Your website could sniff the user-agent tag, and if it found IE6, would redirect the visitor to a page telling them off for running a non-standard browser. The W3C (the World Wide Web Consortium) and WWW godfather Sir Tim Berners-Lee led a crusade against the tyranny of IE6 to almost no avail.

Behind this state of affairs was neurotic logic at the corporate levels of Microsoft that represented the most paranoid reasoning since Richard Nixon on the eve of Watergate. Microsoft had begun the century finding itself on the defense end of antitrust law violations in the US.

Together with the continued presence of Apple, its oldest competitor, and the rise of Linux redefining the web hosting industry, and popularity of Free and Open Source Software, Microsoft executives seemed to feel backed into a corner, fighting ruthlessly for control of the desktop market at all costs.

Refusing to support shared standards fit into that plan. Using the policy of “Embrace, Extend, Extinguish,” Microsoft’s strategy was to enter a market and slowly strangle its standards, replacing them with its own proprietary protocols, until it could use market dominance to bully everybody into doing it their way instead.

They’d done this over and over with everything from programming languages to office document properties. To Microsoft, the World Wide Web was just one more market to choke down and replace.

Ironically, Microsoft’s stubbornness drove the popularity of Firefox, which came along in 2004 like a knight in shining armor. Firefox and Apple’s Safari, released in 2003, respectively brought the Gecko and WebKit rendering engines to the masses, doing everything neatly and compliantly while Microsoft’s Trident rendering engine became the black-hat villain counterpart.

And no matter how much the US and later the EU prosecuted Microsoft for being a monopoly – at one point it was dominating a 98% market share of the world’s computers – Microsoft simply paid the fines out of their deep pockets and kept right on doing it.

All the mighty monopolies fall eventually. For Microsoft, the Scarface-like determination to dominate the desktop forever made them so short-sighted that they didn’t notice the mobile era sneaking up on them. Linux, in the form of Android as opportunistically reshaped by Google, nimbly hopped onto the mobile market.

While Microsoft’s death grip on the desktop market lasted long enough to even choke off the dawn of the HTML5 standard, its position today is that of a fallen empire. They’re still present in the office on the desktop and the occasional consumer laptop, but marginalized in almost every other market.

What else did we miss out on?

Too bad that the mobile-focused market of today renders those standards we were fighting for mostly irrelevant.

Even though Google’s own Chrome browser handles standards just fine, today’s web calls for smooth, flat designs and function over form, since it has to render on anything from a multi-screen desktop to a pocket phone.

There is never a time we’re going to get that Zen Garden movie theater layout or playful robot on our phone, at least not for a major website.

The modern standards of HTML5, CSS3, new Javascript improvements, and support for SVG, have spawned a host of beautiful innovations which will live forever as cute experiments, nothing more. But the toys are there to play with anytime you want them (assuming browser support):

- CSS3 Patterns – Gallery of background patterns

- PatternBolt – Responsive SVG patterns

- The Shapes of CSS – All (?) of the shapes possible to make with just CSS code

- 30 HTML5 games – Very elaborate in-browser games using HTML5

- BrowserQuest – Mozilla’s own HTML5 RPG, in its extensive Hacks section.

- PuzzleScript – An open-source HTML5 simple game engine.

That’s just a taste of what we should have had a decade ago. Some of those examples are even a decade old. And that’s what the future could have been.

The post Who Killed CSS3? appeared first on Design your way.

Source: https://ift.tt/2DhKkF5

No comments:

Post a Comment